3D Anatomy Model

Add another dimension to your learning with fully-interactive educational male and female anatomical models.

Learning about the human anatomy has never been more fun!

Purchase

The larynx or upper windpipe is the body’s organ for phonation or voice production. The larynx is a well-developed organ, it accounts for all verbal communications. The capabilities of the larynx tend to increase as we age. In addition, the larynx is a vital part of the respiratory system, which allows the two-way passage for gaseous flow. As a result, it allows us to speak or produce sounds during the expiratory phase of breathing.

The larynx is located in front of the neck. It extends from the fourth to the sixth vertebrae. In females and children, the location of the larynx is slightly higher. In males, the larynx lies exactly in front of the 3rd – 6th cervical vertebrae.

The approximate length or size of the larynx is 36 mm among females, 3mm in children, and 44 mm among males. In males, the larynx grows and develops rapidly to make a structure called Adam’s apple for low pitched and louder voice at puberty. The internal diameter of the larynx in an adult is 12mm.

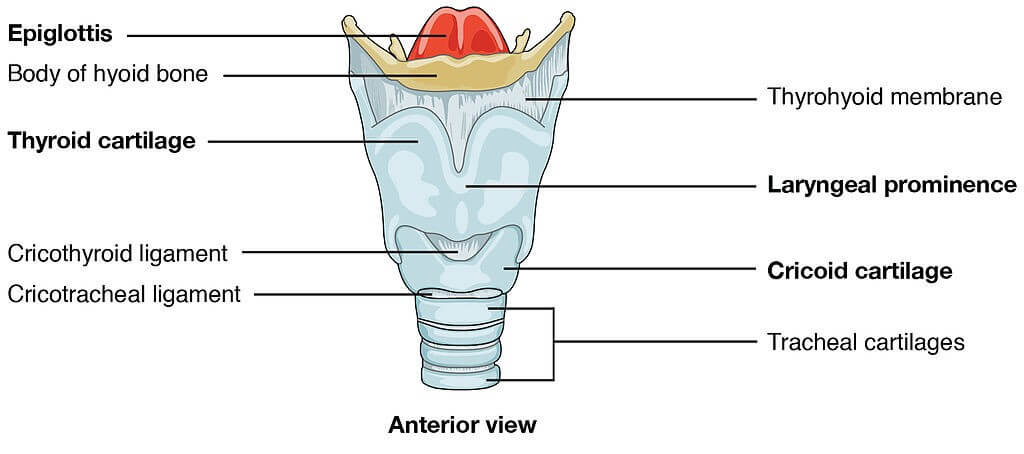

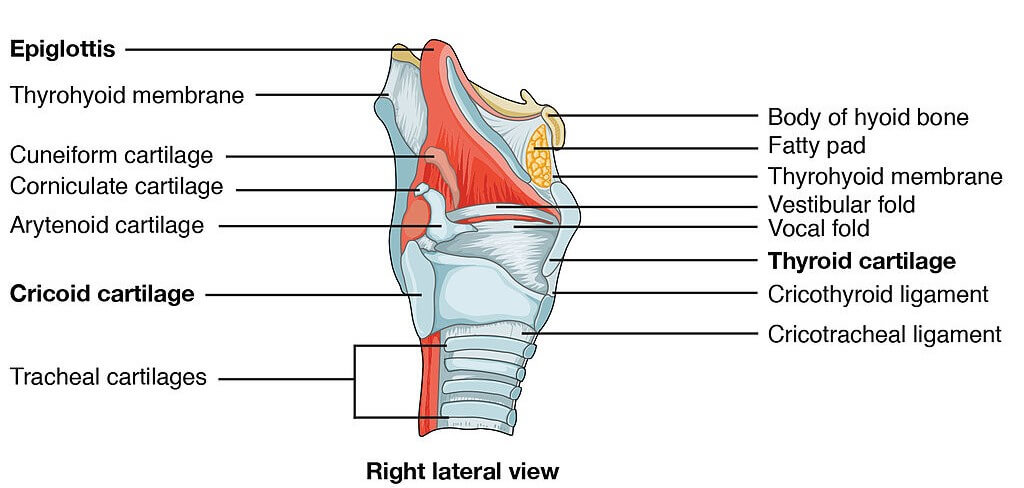

A skeletal framework of different cartilages, known as laryngeal skeleton, makes up the larynx. In total, there are nine laryngeal cartilages in which three are paired, and the rest of three are unpaired as:

Among these different cartilages, we shall look at the thyroid cartilage in more detail.

The thyroid cartilage is V-shaped cartilage consisting of left and right laminae. The thyroid cartilage sits as the uppermost and largest cartilage in the laryngeal cartilages. The laryngeal prominence (Adam’s apple) is the median projection of the left and right laminae of the anterior borders.

Cricothyroid joint forms as a result of articulation of cricoid cartilage and the thyroid. A ligament arises from the cricoid cartilage to attach to the thyroid. The cricothyroid ligament prevents the uncontrolled movement of each cartilage and in the case of upper airway obstruction, a surgery to excise this ligament may be required (emergency cricothyrotomy).

Two joints, the cricothyroid joint and cricoarytenoid joint, work in the larynx

Intrinsic laryngeal muscles include:

The extrinsic muscles of the larynx are the ones that attach to the hyoid bone, thus enabling movement of the thyroid cartilage.

These are a few muscles that act on the larynx to produce different movements such as;

The laryngeal folds are divided into vocal folds and vestibular folds. The folds are divided by a space between them, this is called the Rima glottides.

Vocal fold:

These folds are called true vocal folds because they form the inner walls of the larynx.

Vestibular fold:

Also known as false vocal cords because they sit on the vocal cords to protect the larynx. These folds have no contribution to the production of sound.

Both vocal fold and vestibular folds of the larynx divide the larynx into three parts:

There are four basic processes for speech production:

All the cartilages and membranes of the larynx help in protecting the lower respiratory tract. During swallowing, vestibular folds and epiglottis help in sealing the larynx to prevent the entry of food into the trachea.

Two nerves supply the muscles of the larynx:

The blood supply for all the structures up to the vocal folds is by the superior laryngeal artery. The venous drainage at this point is via the superior laryngeal vein.

All the structures below vocal folds have their blood supply and venous drainage by the inferior laryngeal artery, and the inferior laryngeal vein respectively.

Laryngitis is the infection and inflammation of the larynx on account of the trapping and lodging of foreign bodies. Laryngitis is characterized by hoarseness of voice and a dry cough. Acute laryngitis usually goes away on its own. With chronic laryngitis, treatment is targeted at the underlying condition, such as smoking or heartburn.

Singer’s nodules or teacher’s nodules occur commonly occur in teachers, singers, or pastors. They result from repetitive vocal cords misuse or overuse. They cause callous-like growths that develop in the midpoint of the vocal folds. This leads to hoarseness of voice and a breathy sound when speaking or singing.

Vocal cord paralysis occurs when the nerve impulses to your voice box (larynx) are affected. This causes paralysis of the vocal cord muscles. Vocal cord paralysis can affect your ability to speak and even breathe because your vocal cords do more than just producing sound.

Vocal cord paralysis leads to inappropriate opening and closing of vocal cords and this causes various complications in swallowing, speaking, and breathing.

This is a lifelong condition where the muscles that generate a person’s voice go into periods of spasms affecting voice and speech. In some cases, the disorder is temporary or can be improved through treatment.

This usually follows neck surgery, a neck infection, or a tumor. External laryngeal nerve damage causes weakness in producing sound. In such an injury, the cricothyroid muscle’s tightening or contracting effect on vocal cords is lost.

In recurrent laryngeal nerve injury, phonation tends to completely vanish completely.

The content shared on the Health Literacy Hub website is provided for informational purposes only and it is not intended to replace advice, diagnosis, or treatment offered by qualified medical professionals in your State or Country. Readers are encouraged to confirm the information provided with other sources and to seek the advice of a qualified medical practitioner with any question they may have regarding their health. The Health Literacy Hub is not liable for any direct or indirect consequence arising from the application of the material provided.